I think I’ve discovered something new, and I think I’m gonna call it Robert E. Howard Syndrome.

For those of you who are unaware, Robert E. Howard was a pulp writer in the late 1930’s, a very fascinating individual. He was an asthmatic child, but took up bodybuilding and boxing to strengthen himself. Born in an oiltown in Texas, he lived on a sort of frontier between expansion into the wilderness and something approaching urban civilization. And he made his money writing about this and putting it into stories sold to Weird Tales.

Most famous of his creations is Conan the Cimmerian, also known as Conan the Barbarian. But just as notable is his final king of the Picts, Bran Mak Morn; his philosopher-king from sunken Atlantis, Kull; and his dour Puritan devoted to hunting down evil in all of its forms, Solomon Kane. These and many other characters (Sailor Steve Costigan and El Borak, among others) peppered the pages of the pulps, the cheap and disposable paper magazines full of salaciously adventurous short stories.

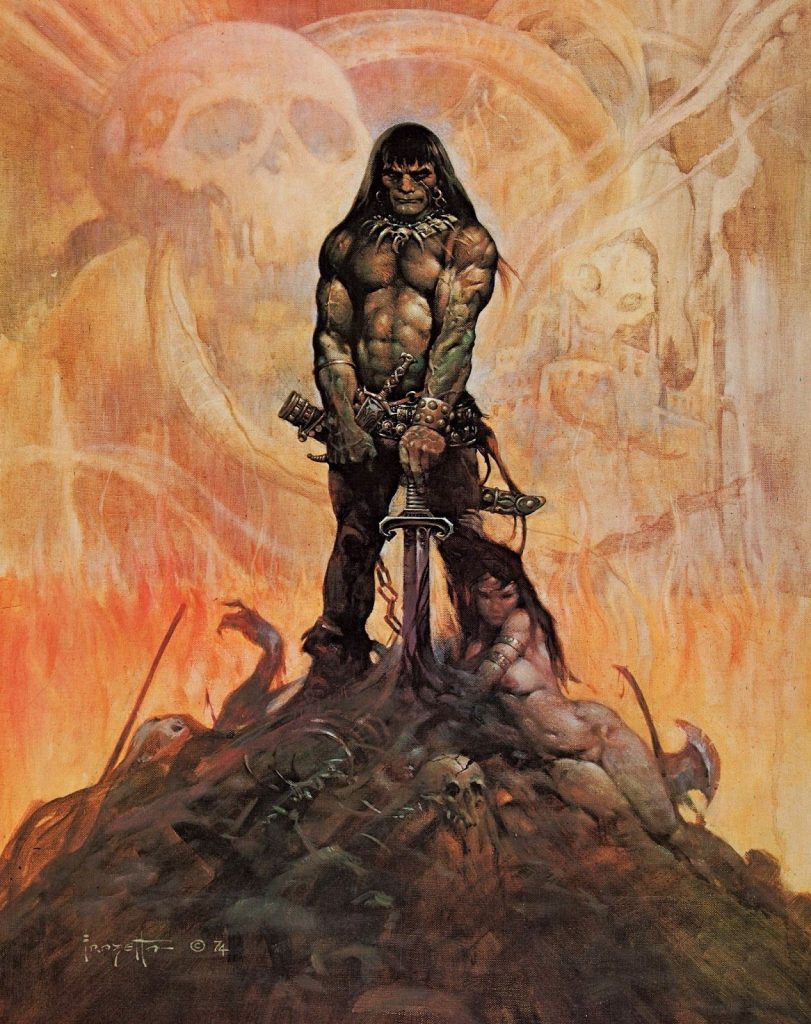

Conan is well known for two reasons. One, after initial publication, the immensely talented artist Frank Frazetta ended up doing the reprint covers for the books. Seriously, look at this painting. While Frazetta has his many imitators (and I might even be able to argue that Frazetta himself is a victim of Robert E. Howard Syndrome), his style is incredibly unique. This set the tone for many a fantasy book cover, and even after

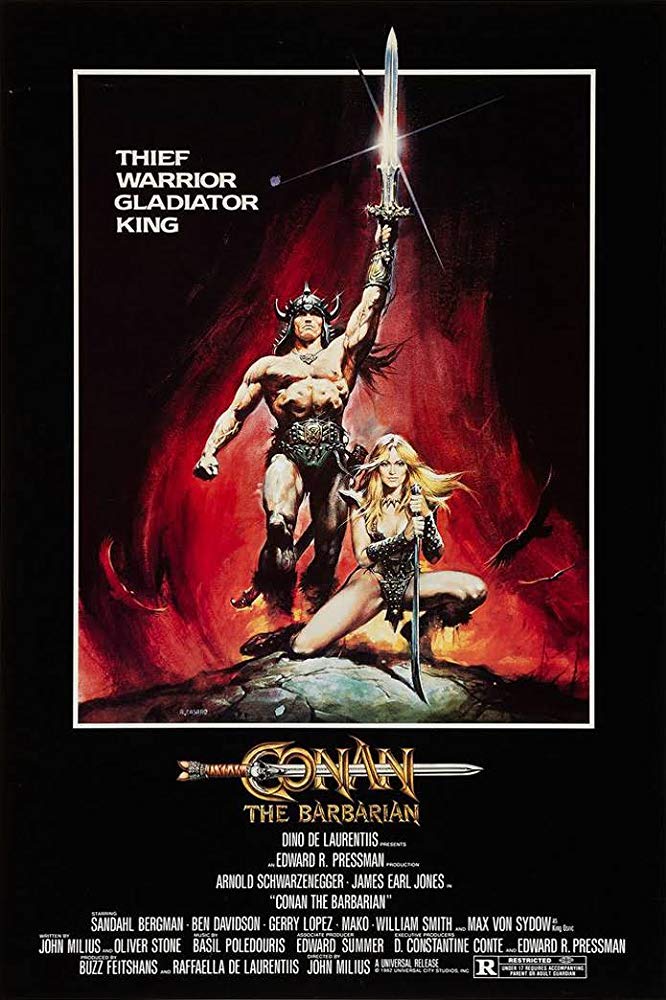

The second reason Conan is so well known is, unfortunately, the source of Robert E. Howard Syndrome itself. This would be the Conan the Barbarian movie, as performed by Arnold Schwarzenegger. Here, the barbarian who stands outside of civilization is rendered into an almost buffoonish caricature. All brawn, little brain, with a propensity to swear by strange gods and bed any woman he comes across. It is, however, still a very fun movie with moments of gold in it (Tell me that James Earl Jones is not spectacular as the snake-enthusiast cult master Thulsa Doom).

Howard was already popular in his time for his stories of adventure, but these two things boosted his popularity. He had imitators too; stories of brawny barbarians and busty wenches began to crop up (including the infamous “Eye of Argon,” a Howardian pastiche infamous for how badly it was written and thus how unintentionally hilarious it was to read aloud). And this is where the Robert E. Howard Syndrome kicks in.

If I asked you, dear reader, to picture Conan the Barbarian, you probably pictured The Governator in a fur loincloth, wide eyes a little vacant. You pictured an idiot, a thug nearly identical to a bandit except he fought for the good guys, running around with a scantily-clad babe at his side and a giant sword in his hand and far too little clothing for the snowy climes he finds himself in.

In other words, you’re picturing someone who’s NOT Conan.

When readers were first introduced to Conan the Barbarian, in the story “The Phoenix on the Sword,” (Weird Tales, 1932), you’re introduced to him not as a wandering adventurer, not as a thief, but as a middle-aged king; a king with wisdom, in fact (advising his adviser to avoid persecuting a certain subversive poet in his kingdom, for the barbarian knew such actions would no doubt earn that poet immortal fame). The next story has him in a more familiar role, a wandering sellsword pursuing (or being bewitched by, it is a bit unclear) a woman (“The Frost-Giant’s Daughter”). The next has him as a king again, but a king captured, a king fighting his way out of a devilish sorcerer’s house of horrors (“The Scarlet Citadel”). The next one has him as a young man, questing for glory and joining a master thief in stealing a legendary treasure (“The Tower of the Elephant,” one of the two of my favorites.). The next has him fall in love with a pirate-queen, whose romance ends with a fateful voyage to a deadly swamp (“The Queen of the Black Coast,” the second of my favorites.)

So of those, two of them are of him as a king, one has him as a young man (not the brawny barbarian one imagines), and two have him in more of the stereotypical role you imagine Conan in. Now that we’ve shown you that plotwise Conan did not fit the characteristic Brawny Barbarian stereotype, consider the writing. Far from the hackneyed and awkward prose one might imagine, Howard had a gift for description and employed a very active style.

TORCHES flared murkily on the revels in the Maul, where the thieves of the east held carnival by night. In the Maul they could carouse and roar as they liked, for honest people shunned the quarters, and watchmen, well paid with stained coins, did not interfere with their sport. Along the crooked, unpaved streets with their heaps of refuse and sloppy puddles, drunken roisterers staggered, roaring. Steel glinted in the shadows where wolf preyed on wolf, and from the darkness rose the shrill laughter of women, and the sounds of scufflings and strugglings. Torchlight licked luridly from broken windows and wide-thrown doors, and out of those doors, stale smells of wine and rank sweaty bodies, clamor of drinking-jacks and fists hammered on rough tables, snatches of obscene songs, rushed like a blow in the face.

-Robert E Howard, “The Tower of the Elephant,” Weird Tales March 1933 ed.

Now this, rather than the desaturated wildlands of the Conan movie, sounds interesting. A tavern-hall full of shady characters, where the watchmen didn’t even bother to go… there’s potential here. So why is this not what we think of?

Enter Robert E. Howard Syndrome.

Robert E. Howard Syndrome is the unfortunate event where an excellent artist or author creates a work so transformative and influential that he spawns more imitators, and that these imitators (of inferior quality) end up producing a corpus of works that clouds the legacy of the original artist. Or, if you’d like, you can break it down to a formula:

Robert E. Howard Syndrome = (Popularity + Imitators + Depth) + Time.

Depth, you may ask, why is depth important? Depth is what the imitators don’t get. If you asked someone off the street what Conan is about, they’ll probably say it isn’t really about anything, it’s escapist fiction. That’s true of Conan imitators, but Robert E. Howard had his stories mean something. He explored the flaws and the tangled webs of civilization, placing Conan outside it. Civilization, he argued, would lead to decadence, and a rugged, barbaric individualism would assert itself after civilization’s collapse. All this in adventure stories that are still ripping good yarns.

But these themes were lost on the imitators. Like the Conan movie poster above in relation to the Frazetta cover, they capture the style without any of the substance. They had busty wenches and brawny barbarians, lots of death and dismemberment, but they were missing something. They were missing the themes of Conan (a rebuke, in some respects, to his pen pal H. P. Lovecraft’s despair, what later came to be called Cosmicism), but they were also missing the tone. Howard wrote his life, living in a strange mix of wild frontier and civilized town, into his work. He put himself into the stories, and that’s what the imitators could never do. And they never should have tried.

For one thing, they’re not Robert E. Howard. They should have put themselves in the work, taken a new spin on the tradition that Robert E. Howard created. Writing in a literary tradition, especially intentionally, does not mean one must sacrifice the individual quirks and specialties that makes the writer unique. Fritz Leiber knew this, and his Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser stories were, while definitely in the Conanesque tradition, their own thing.

The Eye of Argon, on the other hand, slavishly obeyed the genre conventions and tropes without a second thought or, more importantly, without knowledge why those tropes were employed in the first place. Besides the terrible writing, it was that pristine unoriginality that damned the work. Slavishly obsessing over the tropes without regard as to why they were employed leaves the tropes feeling phoned in, vapid. “Of course my work has orcs, all fantasy works have to have orcs,” for example, or “Of course my barbarian has to have a giant sword, that’s what they all have to have.” There aren’t rules for these things, and while you can have orcs and barbarians with giant swords in your works (and I have both in abundance) it will serve you much better to put some thought behind it. Conan’s barbarian was incredibly intelligent, but merely uncivilized, which made him the prime candidate to point out some of the absurdities of civilization, as Howard saw them.

Robert E. Howard Syndrome is an unfortunate side effect, where the bland and unoriginal pastiches of a work end up coloring the original’s perception. There is one way to counter this, and that is to find the originals and approach them with an open mind. Force yourself to forget the Governator in a fur loincloth, and read “The Phoenix on the Sword.” Forget the tropes that have ended up becoming parodies of themselves and read the originals that inspired them. What will happen, nine times out of ten, is that you’ll realize that what you’re reading isn’t what you expected. And you might even like it.

Recent Comments